|

Want to read on the go? Listen to the article instead

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

A good book will hunt you down, and that is what Muti Michael Phoya’s book did on a solemn Monday morning. I stumbled into KwaHaraba Café, one of my favorite cafés in Blantyre. I was to wait for someone as they took their calls, and with the fear of boredom, I zeroed in on their bookshelves, hoping to find a book that would intrigue my mind.

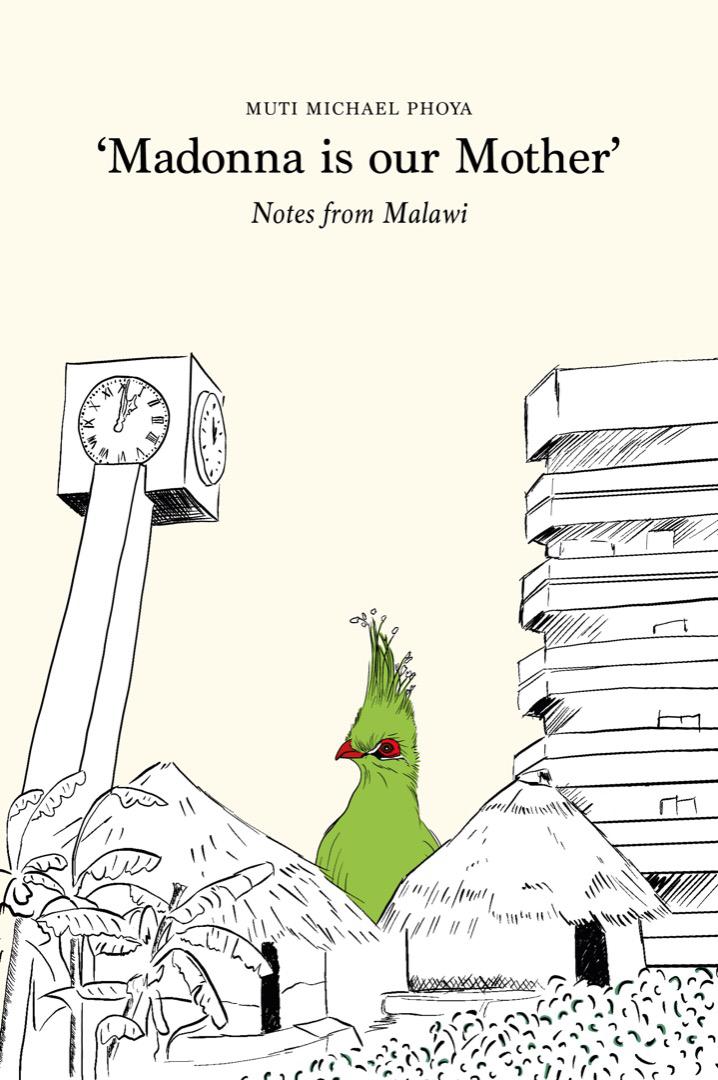

Not only that, but I had not heard of a few on the stand that houses books about Malawi. Flipping them over to the back, I quickly read their blurbs. Almost losing faith, a nude-colored book caught my attention. On its cover is a black and white drawing of the Clock Tower, a building resembling the Chayamba, mud huts, and banana trees. At the center of the drawing is an angry-looking green peacock that would easily give you a nightmare.

However, it was not the peacock that made me pick up the book; the title brought so many questions to my brain that I wanted to be answered. <strong>’Madonna is our Mother</strong>'<strong>: Notes from Malawi</strong>, it simply read. I toyed with the title in my mind for a few seconds; had he written about how people on social media had fantasized about being adopted by Madonna to escape the hardships of Malawi? Was it a book that was going to idolize the Global star of Raising Malawi? Or was this a book criticizing her about how she was raising the Malawian adopted kids and the outcry on social media?

Without reading the blurb, I sat at my table and allowed my mind to get lost in the words while having my coffee. The coffee was amazing, by the way, in case you were wondering.

What I discovered was I had just bought myself a history book, with a point of view that more than intrigued me. It did not take me long before I decided I needed the book in my collection and bought it. All I can say, Muti Michael Phoya took his readers on a journey.

Muti Michael Phoya’s ‘Madonna is our Mother’

This book is a compilation of essays penned by Muti, focusing on pre-colonial history, how it marries into post-colonial events, and ultimately how Malawi happens to be where it is in this day and age. As the blurb of the book states,

Muti presents some thoughts on the shifting character of post-colonial Malawi. Focusing mainly on the land and memory…

Madonna is our Mother

The essays offer a matter-of-fact tone, laced with some dry humor, with an undertone of an author who is not only trying to enlighten but also trying to make sense of their society and how it has come to be. It offers a free history of the country, some of which can only be accessed by those truly interested, as it has been scrapped from our history lessons.

The first chapter titled ‘Geo-Spatial Verities’ introduces us to the dirt roads of Lilongwe and the influences of colonialism still present today. Reading through this chapter, you notice that all Malawian cities are planned the same (read ‘planned’ very loosely). Funny enough, this chapter alone summarizes some discourse that Malawians have been having recently on different social media platforms.

Discussions about the recent architectural designs of rising urban areas such as new Area 43, which has the most expensive-looking houses that lack character. They are great signs of money spent, but often are ridiculous to the eyes. It shares how these rich areas are the closest to the poorest neighborhoods.

The biggest example has always been the contrasts between Nyambadwe and Ndirande, BCA Hill, and BC “ele” or Bangwe.

However, it is the issue of street names hinted at in this chapter is one that was recently discussed in Parliament after the president’s State of the Nation Address. In the recent SONA, the president shared that a highway in Chikwawa is being planned for construction, and shall be named the Sidik Mia Highway. Sidik Mia was the Malawi Congress Party’s vice president during the 2019 elections and was chosen as a Minister of Transport after the Tonse Alliance’s election in 2020.

He died serving as a minister, and while he made contributions to the political section of the country, none is prominent enough to warrant a road to be named after him.

While Muti might not have been talking about these very recent events, it is a sign of how as a country, we are regressive.

It is the second chapter that I was truly anticipating as it is where the book got its title from. In ‘Madonna is our Mother’, Muti shares the idolization that the country has for foreigners, and their organizations (read NGOs). Perhaps, my happiness came from what was shared about Rev. John Chilembwe.

In his dry humor, he puts into perspective the arguments that ensure each year as the 15th of January edges closer, and on the very day. He shares how the country becomes divided, with some stating John Chilembwe’s uprising was years early and should have taken place later, while some back the dear Rev for his actions.

For some of you who might not be aware of this argument, many Malawians believe if only John Chilembwe had kept his calm and waited, maybe Malawi would have been developed like the likes of South Africa. He has been blamed for his ‘impulsiveness’.

What I found beautiful about this book is it explains what pushed John Chilembwe to the edge. In the chapter, ‘The Legend of John Chilembwe’, he shares part of a letter penned in 1914 by Chilembwe himself. I quote

…In times of peace, everything for Europeans only… But in time of war [we] are needed to share hardships and shed blood in equality.

Madonna is our Mother

To then have his countrymen, 100 years later, blame him for staging an uprising against the whites, and the conditions Malawians were subjected to is nothing but betrayal (in my honest opinion). But again, it cements Muti’s frustration for praising Westerners more than actual heroes in the country.

Of John the Baptist and Kamuzu Banda

Very recently, I saw a tweet that said history should be scrapped from the Malawian syllabus and more focus be given to Information Technology. I took some time to share with the author the importance of understanding the country’s history to progress.

I am a firm believer that Malawians are yet to make sensible decisions with their social-political landscape because of the lack of understanding of our past, and the changes needed to ensure progression.

The former president of the country, Dr Bakili Muluzi once said that “Malawians are quick to forget” and that was factual. Muti too expresses the same sentiment in different essays, with some more undertone than others. In the chapter ‘On /Off Things Remembered’, he says

This piece is about selective memory. This piece is hinged in that space that seeks the familiar… Memory is often selective, the uncomfortable shoved in the background…

The world is always simpler in the past, its projection always linear. Except in spaces like Malawi, where development lags. Where in most spaces the past and the present merge, to become idyllic.

Madonna is our Mother

However, the most thrilling was reading how Kamuzu Banda might have done one of the best brainwashing jobs on Malawians. Muti shares how Kamuzu used biblical notes of John the Baptist and his preaching of the coming of Jesus. Then cooked his story to best fit that narrative.

How Chilembwe was portrayed by Kamuzu as his John the Baptist, thus making himself the Jesus of Malawi. That’s why, to date, we refer to him as the founding father of the country when all he did was reap the fruits of the blood and sweat of others. While those who worked hard to see the country free are given backhanded compliments, with not much thought given to them.

This is the selective memory that we have chosen to carry over as a country.

Of dry humor and relativity

Madonna is our Mother is filled with dry humor, one that can easily escape others. It is so deadpan, but somehow, it brings breathers to the information vomit that the book offers. One of my favorite lines comes from the essay ‘Malamulo, 20 Years Later’ where Muti says

We drive on, passing the girls’ hostel… As sexualized teenagers, it is a place for many a fantasy… A classmate of ours once loudly imagined if one’s male private parts could be thrown into such a place, only to come back a little later.

Madonna is our Mother

Regardless, that he was sharing his journey back to his former secondary school, is probably a story many have taken. To different schools, you get the gist. A lot of people who have attended missionary schools, or once-prominent government schools, get jarred by the state of the schools now.

Most schools that were once glorified, are now just shadows of their past glory. That is one of the moments you will find this book relatable. While I have never visited the last two schools I attended (forms 2–4), my recent visit to the school I went to when I was in form 1 was so nostalgic. Albeit not jarring, but I reckon one of the two remaining could be in a bad state.

Likewise, the shock Muti and his family have in the essay ‘On/Of Things Remembered’ as they climbed the Zomba mountain and noticed how bare it had become compared to the past. We recently had the same experience as we drove up during my son’s 2nd birthday celebration.

Seeing the state of the mountain, the number of trees that had been cut down, and realizing that we could now see the Zomba town in full view from up there, a view that was once hidden, is upsetting. Reading this felt like reliving the moment.

Overall, this compilation of essays by Muti Michael Phoya was so well curated, offering free history classes for those with curious minds. Muti flexes his knowledge of the history of the country, not in a condensing manner, the depth at which this book goes truly shows his need for the reader to understand where we are coming from in order to make sense of the state we are in right now.

If anything, it made me feel bad that I still haven’t read the Rose Lomathinda Chibambo book.

I need to get my hands on this book. An honest and valuable review by the way.